How to Make Animal Rennet

Building self-sufficiency skills for the cheesemaker

I have been interested in learning how to make rennet for several years. The increasing discussion over food shortages and supply chain issues has really pressed upon me our dependence on cheesemaking ingredients. While I know I can create (imperfect) mothers from the cultures I have stocked, if I lose access to rennet there is no longer a way for me to store milk long-term and make cheese. But, not only am I dependent on rennet to make cheese, I’m dependent on an international source for non-GMO animal rennet. Not very sustainable. (While there are companies selling rennet in the US, it appears that these are resellers and, with rennet being a perishable product that weakens over time, I prefer to go straight to the supplier to ensure the freshest possible product.)

The trouble is, with so many little children I knew they weren’t going to easily budge on the Fluffy Animal Scale of ethical and humane standards. (Most adults won’t budge either to be fair.) This year I was finally able to rationalize with them and they conceded that “cuteness” was the only factor that separated what made it “ok” to kill a two-year-old steer, but not a 2-day old calf for food.

The simple fact is, if you like cheese on your pizza, shaking parm over your spaghetti, and a creamy bowl of Mac & cheese, you’re either eating a GMO food or a baby animal had to die for your dinner. If neither of those options is acceptable to you, it’s time to walk away from the wedge.

To shudder at harvesting a new calf on the farm is not really different than the folks who like shopping for meat from the grocery store cause they don’t like to think about where it comes from. It’s just further up on the food morality continuum. I’m trying to put my family in a proper relationship with their food. Food isn’t cheap. Food isn’t fast. Food requires death.

“Our sustenance is completely and utterly dependent on taking life, be it plant or animal. That alone should drive us to appreciate the sanctity and precious value of life." - Joel Salatin

The resulting mind shift is one that causes my heart to ache when there is waste. I have two Gruyere cheeses right now that will go to waste because I followed a bad recipe (then thought I could fix it.) The lost time over the cheese pot. The lost morning’s milk from two cows. The lost dose of rennet from a calf’s abomasum. Having pigs on the farm is a consoling balm because there never is truly any waste. The food simply takes another form than I had originally intended. Taking responsibility for the lives that feed your family includes hard decisions about the future of those lives, and not passing the responsibility off to another farmer or the butcher when we are uncomfortable.

The Conundrum of the Bull Calf

On our farm, we typically breed our cows using sorted semen. This increases the likelihood that the calf born will be a heifer and we will be able to offset some of our feed expenses from the year by her sale to a new home. But, it’s not always fail-proof and Heidi has still managed to defy the odds and give us a bull calf not once, but twice in a ro after being bred with sorted semen. This month we put her two-year-old steer in the freezer and her new bull calf was harvested for rennet.

This was our second calf to harvest for rennet. We also took Indie’s summer calf for the same purpose and that experience is, ultimately, what doomed the new calf to the same fate once it was discovered that “she” had man bits.

The conundrum a bull calf presents for the family cow owner is really no different than it is for a large producer. We’re both raising a dairy cow for the... dairy. Sure a bull calf can be raised for homestead beef. But when you get multiple bull calves in a row will you have enough pasture to support them, keep your dairy cow in good condition, and be able to put flesh on the calf?

For most of us with small acreage, that answer is, “No.” Add to that- pound for pound, two pigs can grow out as much flesh in less than one year as a steer can in two, on far less land. (Case in point: we put away two 10-month old hogs and a two year old steer this month. The hanging weight on the Hereford hogs was 508 pounds. The Jersey steer was 562 pounds.)

The problem of the bull calf is something one must consider before jumping into family cow ownership. A bull calf at the sale is lucky to fetch a high enough price to fill the gas tank to get there and back + the trailer rental. The yield on veal seems hardly worth the work and expense for the homesteader. For the cheese maker, the stomach can be harvested to make rennet and remove a dependency on the global food system.

These are things to consider when you have a home dairy- it’s not all golden butter, frothy glasses, homemade ice cream, and a fridge full of cheese wheels. You will have to make hard choices and not allow your emotions to rule your spirit.

Indie’s Calf

When Indie’s calf was born I spent days researching how to make rennet.

Perhaps one could justify raising Jersey beef but Guernsey? Indie is a bag of bones and nothing I try gets her to put on flesh. To raise him would be a waste of precious homestead resources. His greatest value would be in learning to make rennet and to use the whole experiment as a teaching tool so others could learn.

I was shocked at how little information is available in even the most technical of cheesemaking books. After defining rennet and offering a summary of how it’s made, most simply point one to the ready availability of rennet from suppliers. I charted out notes and formed a game plan.

I chose three methods I was interested in trying and divided the abomasum into pieces to process each differently. And so began a 5-month long process of trial and much error, frustration, disappointment, and finally squealing- and dancing-worthy success.

How to Make Rennet - Three Methods

Brine & Dehydrate

For this method, it was said rennet was made by packing the stomach in salt. Water would be pulled from the tissues to form a brine. There were no specifics on how long to brine the stomach so I left it until it was convenient to manage, after harvest season, about 3 months. The stomach is then dehydrated. It took 3 days in the dehydrator and the final product was very crusty and brittle. It easily crumbled apart.

Dehydrate & Pack in Salt

Just as it sounds, the stomach piece was rubbed with salt and dehydrated. It also took 3 days to dehydrate. Afterward, it was cut into small pieces and packed in salt. It was said this would last for years. I prepared two pieces this way. One was stored in a jar, the other in the freezer.

For both of the above methods, the pieces are broken or crushed and soaked in whey prior to cheesemaking.

Make a Stomach Paste

For this method, the stomach piece was weighed and placed in a brine proportionate to the quantity of stomach. (Already, this method was appealing to me… Weighing always seems like a pain in the rear but there’s nothing like busting out the scale to reassure a body they’re going to get consistent results.) After brining for a few days, the stomach is dehydrated, powdered, and stirred into whey slurry before being strained. The liquid is reserved to be used in cheesemaking. For more detailed instructions, I shared more specific instructions for the Homesteaders of America readers.

The stomach paste was by far the quickest method and I was excited to see it wouldn’t require forethought to prepare the rennet for cheese day. I can barely remember to defrost meat for dinner. Prepping rennet? Not likely!

A friend shared with me David Asher’s method that has been updated since he wrote his Natural Cheesemaking book. Since it requires the entire stomach, and I was feeling experimental, I opted not to try it. In a nutshell, it is also a Brine & Dehydrate method. He ties the sphincter ends of the stomach, complete with all of the undigested contents, and packs it in a container with an equal weight of salt. It too forms a brine and is left for 3-4 months before being hung to dry. It is said to last for 2-3 years.

Asher also spoke of a French method whereby the stomach was cleaned out and inflated to stretch it like a Little House on the Prairie pig bladder. Another source claimed a Mediterranean method is to rinse the stomach and fill it with milk before setting it out to dry in the hot sun. The white powder is to be used as rennet. (How flies aren’t an issue in the absence of salt is beyond me.)

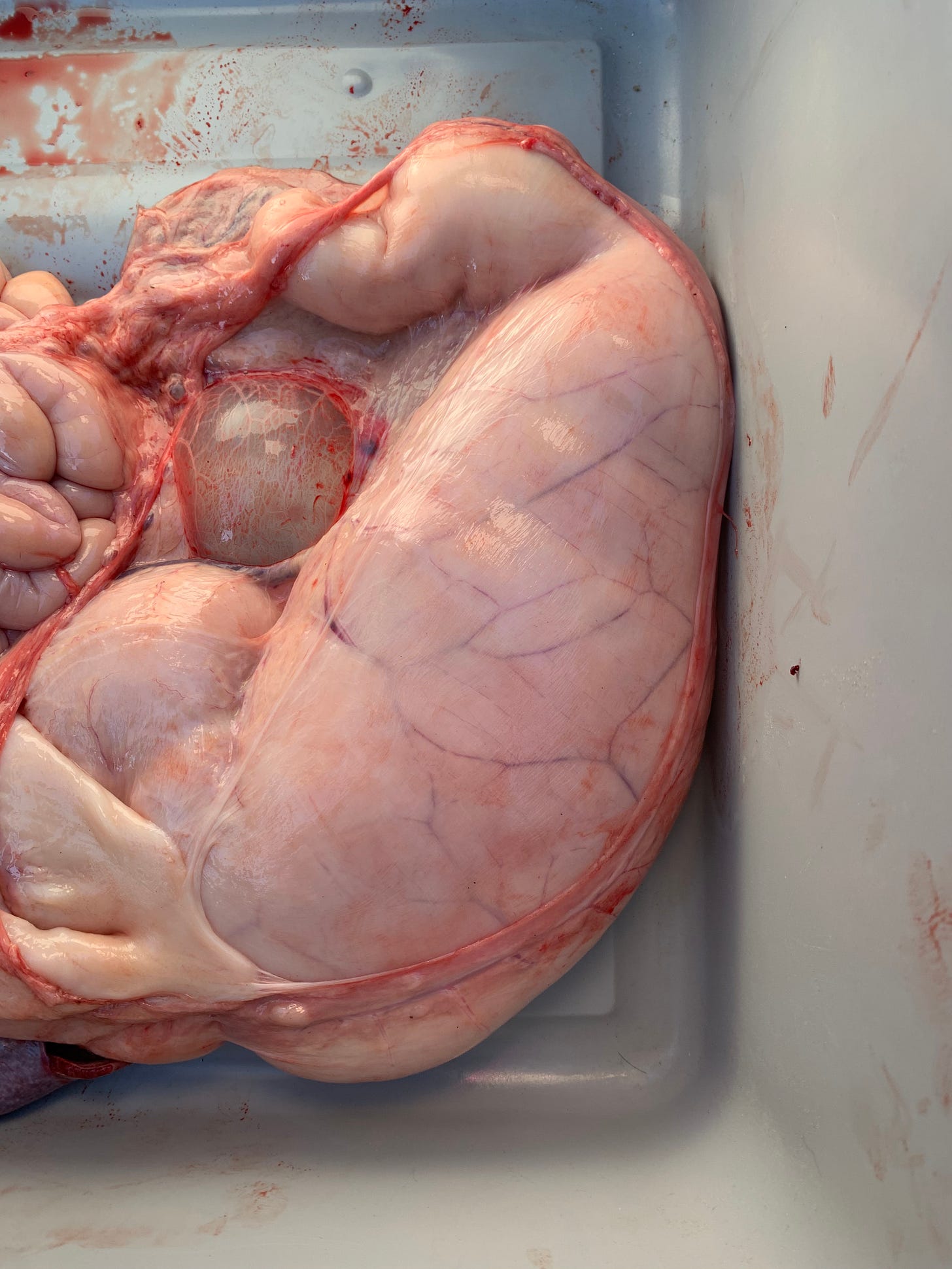

Identifying the Abomasum (PHOTOS)

There are four chambers to the stomach in the ruminant… only one will make rennet. How do you know which to use?

First, it must be stressed that once the animal has started drinking milk, the younger it is, the greater the strength of the rennet will be. The first week is preferable. We harvested the first calf when it was 15 days old. Though one of the methods produced a sufficient rennet strength, it was late enough that the other methods failed. The second calf harvested this year was taken at 3 days old and the rennet worked as it should. The difference? Already at three days old, there were tiny bits of grass in the stomach. Over the next two weeks, he would have nibbled grass in increasing amounts and the enzymes in the abomasum would continue to weaken in order to shift the digestive system to a grass diet.

At this time, the abomasum is the largest of the stomachs. Interestingly, inside each of the stomachs vary in the appearance of the walls.

The rumen (not pictured) is something like a sea sponge inside. The reticulum has a honeycomb shape while the omasum and abomasum are like folds of silk, with the abomasum being larger, more pronounced, and abundantly folded. Inside the abomasum, you will like find both liquid milk and curdled cheese. Here are some good photos of each chamber's interior.

The Results

Once the abomasum pieces were fully processed, I went through gallon after gallon (after gallon after agonizing, frustrating gallon) of milk trying to discover the correct ratio of stomach to whey. I was adjusting how long to allow the pieces to soak, one day, 3 days, 5 days, 7 days, 2 weeks? Does cornmeal work to strengthen it as I read in a forum? I tried whey brine, fresh whey, whey from clabbered milk. Covered, uncovered. Nothing seemed to work. It was to the point where I threw dosing out the window and, after missing any reasonable flocculation target, dumped the rest of each batch into the pot and left it overnight to see if it would coagulate. Only once did it work overnight- and that was for the Dehydrate & Pack in Salt frozen pieces. And when trying to zero in on that method, I couldn’t get a small enough ratio, soaked long enough to work (save for that one overnight.)

Except for the stomach paste.

The stomach paste method was successful but it was still slow to coagulate. While the other methods didn’t coagulate at all, the stomach paste flocculated in 50 minutes for a total curd set time of 150 minutes for a cheddar, far too long to make good cheese. (The commercial rennet control, Danisco brand, flocculated in 14 minutes for a total curd set of 42 minutes.)

Two reasons for the extended time could be (1.) Because the first calf was 2 weeks old; and/or (2.) Because I had diluted the stomach too much. (The first calf was done at a ratio of 1 part stomach to 16 parts whey; the second was done at 8 parts whey to play it safe. If I feel mathematical one day I may try to take some of the second calf’s rennet and dilute it further to see how far I can stretch it.)

Because I think this information is so important I shared the steps I used to successfully make stomach paste rennet with a far larger reach of homesteaders on the Homesteaders of America blog.

growing up on a farm we did it all, which meant we understood and were naturally educated in animal husbandry from start to finish in all its glories. The process of cheese making has become extremely sanitized and G-rated that it is hard to see or locate the reality of life and death on farms that benefit us. Thank you for being brave "as Lisa stated" and going into the minutiae that make up natural/historic cheese making.

I'm thrilled to have stumbled onto your article about making rennet from the Homesteaders of America Newsletter. I couldn't wait to sign up for your sub stack to explore more about the kind of woman who would bravely write about making her own rennet. I'm now enthralled with the content I've discovered so far, barely getting started... My hats off to you friend, in courage and in truth - a new subscriber - Lisa (beginning our 13 year with dairy cows and the whole farm thing so... ya, not that many of us - nice to find a kindred spirit. :)